Urals fleet constraints more likely as sanctions enforcement ramps up

An exodus of EU-operated vessels and an overall shrinking in fleet size points to increased capacity restraints for the fleet carrying Russian Urals.

Last week was a busy one on the Russia sanctions front. New rules on the price cap scheme came into effect whereby tanker operators must submit attestation documents per voyage instead of annually to prove compliance. A few days later, the UK announced sanctions for key operators in the Russian trades, and the US announced sanctions on Sovcomflot and its tankers. These events have understandably raised questions about capacity constraints for the fleet transporting Russian Urals. We observe a fundamental shift in both the size and the profile of the fleet trading Urals, which points to the increasing likelihood of fleet constraints and a higher degree of segregation between the Russian-traded and the “mainstream” fleet.

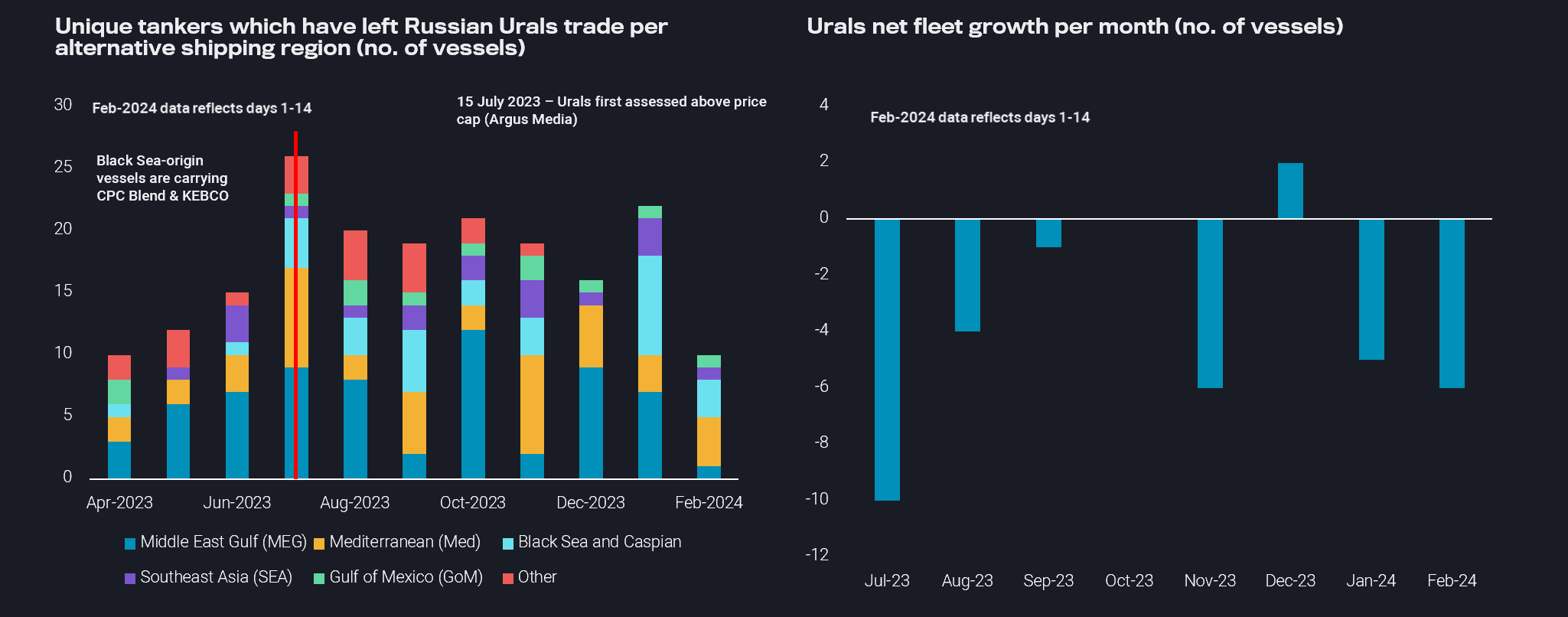

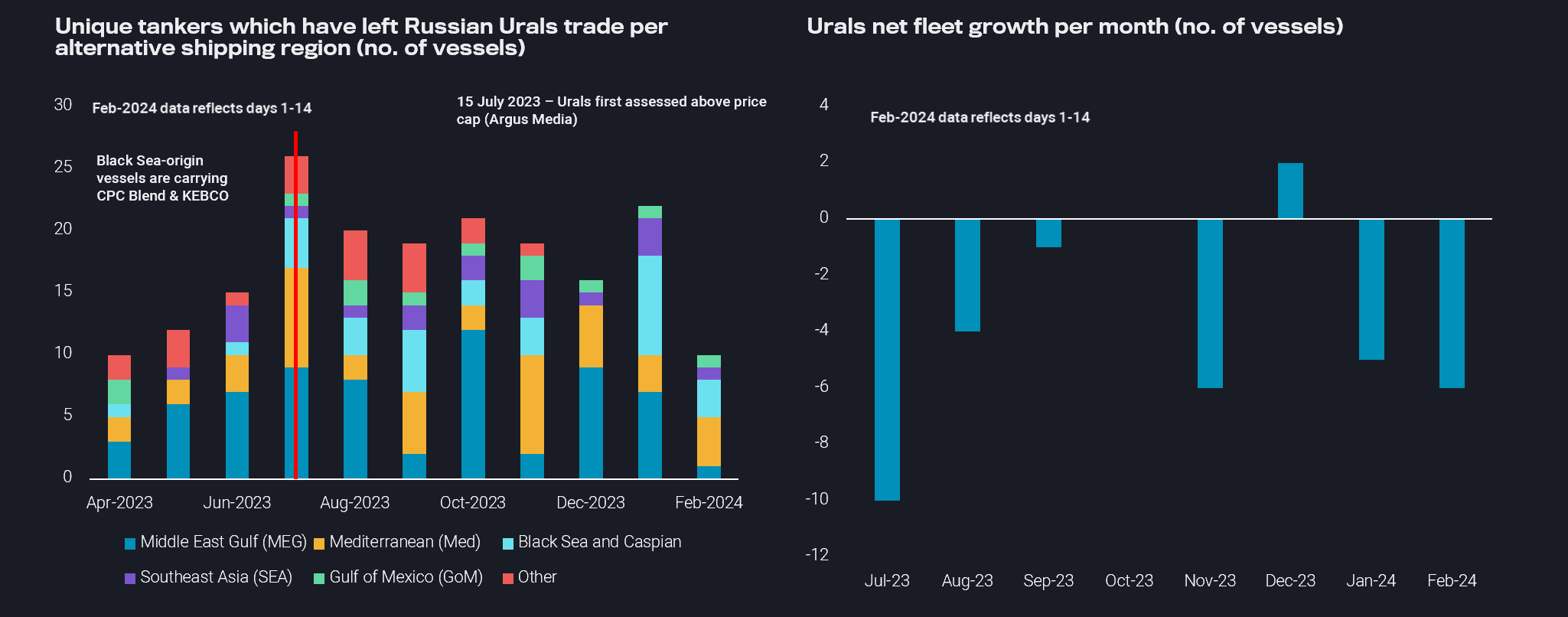

Since Urals was first assessed above the $60/barrel price cap in mid-July 2023 (Argus Media), the number of tankers leaving the Urals trade and not returning increased considerably, averaging 20 tankers each month through January. At the same time, this is not matched by new tankers joining the Urals trade, meaning that the Urals fleet has suffered a net loss of an average of 3.5 tankers every month through January. The notable exception was December 2023, resulting from an influx of sanctioned tankers coming from the Iranian and Venezuelan trades.

The stringent sanctions enforcement as well as pricing largely remaining above the price cap since July are clearly behind shifting dynamics when it comes to the nationality profiles of the Urals-linked fleet. The proportion of Greek operators in the Urals trade was 39% prior to mid-July 2023. Over the past two months, the fleet trading Urals was only 19% Greek-operated. Difficulties in remaining sanctions compliant has led to an exodus of EU operators, while the share of operators linked to Russia, China and low-tax sovereigns has increased notably. The change in fleet composition plus the overall fleet shrinking points to increasing constraints on fleet capacity, especially as India has recently indicated an unwillingness to accept cargoes from sanctioned tankers.

Chart: Unique tankers which have left Russian Urals trade per alternative shipping region (no. of vessels, LHS chart) and Urals net fleet growth per month (no. of vessels, RHS chart) (Retrieved via Freight API/SDK)

In contrast to the Urals trade, Russia Far East grades (ESPO blend, Sokol and Sakhalin blend) overwhelmingly end up in China. Prior to India refusing to take Sokol cargoes from sanctioned operators, Russia Far East grades lost market share in terms of tonne-mile demand to India beginning late Nov 2023. In Jan-Nov 2023, Russia Far East grades average tonne-mile share to India was 43%, whereas in Dec 23-Jan 24 this share dropped to 19%. After tankers discharge Russian Far East grades, most vessels immediately ballast back to Russia Far East to load again. This suggests a mostly segregated fleet employed on the Russia Far East-to-China route, which will likely be unaffected by more stringent sanctions enforcement on vessels carrying Urals above the price cap. The relatively small involvement of EU operators (11% of all tankers that have loaded since Dec 2022) and high involvement from Russian, Chinese, and low-tax sovereign-linked operators (65%) suggests fleet constraints due to sanctions are unlikely.