Takeaways from the Vortexa and Eurasia Group Webinar: The future of Russian oil exports

The Vortexa and Eurasia Group webinar on 9 February proved to be an essential watch for anyone needing to understand the impact of reshuffling Russian oil flows on a global and geopolitical scale.

It was a great pleasure to join forces with Henning Gloystein, Director, Energy, Climate & Resources for Eurasia Group, and my colleague Pamela Munger, Senior Market Analyst at Vortexa. Our webinar was attended by an unprecedented number of highly engaged attendees – many thanks for all the questions and contributions!

Below you can read the key insights from each speaker, or register to watch the full recording on-demand.

Insights from Henning Gloystein, Director, Energy, Climate & Resources, Eurasia Group

- Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the ensuing weaponisation of energy supply, including Russian gas supply cuts to the EU, western-led phase-outs and price caps on Russian oil supply, means Europe has lost what used to be its biggest supplier of fossil fuels.

- Since the start of the invasion in February 2022, the conflict has only escalated both militarily and economically. Eurasia Group sees little chance of a credible peace deal in the near future since both sides still believe they can win the war, and the maximum compromise either Kyiv or Moscow is to give for a ceasefire remains totally unacceptable to the opposing side.

- Even if there was a surprise and credible ceasefire soon, Moscow’s credibility has been too seriously undermined in Europe for there to be a return to business as usual that would allow for a resumption of significant gas flows to Europe (the damage to the Nord Stream pipeline gas systems to Germany is also too extensive for a return to pre-war flows). For oil shipments, however, a resumption of Russian crude and refined products may eventually be possible, although this would only likely be the case after lengthy negotiations and proof that any ceasefire has credibility.

- This means that world oil markets must plan to adjust to the new reality, which is that Europe will buy little to no seaborne Russian crude or products, and that there will be a price cap by a G7-led group of countries that is enforced by the maritime insurance industry that largely abides by EU law.

- This G7-led price cap and the EU phase-outs try to avoid disrupting global crude and product flows as this would likely cause price spikes and further fan already high inflation. Disrupting global oil flows through western sanctions would also undermine the US and EU position in emerging markets as Moscow could blame Washington and Brussels for the disruptions and price shocks these have caused.

- Instead, the EU and G7-led measures are aimed at reducing oil revenues for Moscow, which it uses to finance the invasion of Ukraine by cutting out what used to be Russia’s biggest market (Europe) and instead forcing it to sell their oil elsewhere at steep discounts.

- These discounts are also aimed at making it easier for non-aligned emerging markets, especially India, to indirectly abide by the sanctions (buying discounted Russian oil is an easier sell for the US and EU than demanding India stop buying Russian oil altogether). This is an important geopolitical element especially for the US, as India has made it clear that it considers the Ukraine war a European conflict, in which it does not wish to be involved either politically or economically, and that New Delhi might suspend US-led security cooperation in the Indo-Pacific should the country be negatively impacted by western sanctions against Russia.

- Opposition to Russia sanctions by China and India, the world’s two biggest nations and rising geopolitical powers, is also the reason why it is unlikely that the US will impose punitive measures (known as secondary sanctions) for not abiding by the G7-led measures. Washington simply cannot afford to antagonise India in the Indo-Pacific, and it currently does not wish for a further deterioration of its already poor relations with Beijing. As a result, US or EU measures against significant sanctions breaches are more likely to be targeted at individual companies (e.g. shippers), or at more closely aligned nations, including NATO-member Turkey.

- The overall impact of the Western crude and product phase-outs and price cap is therefore likely to be limited. The measures have caused costly dislocations by forcing Russia to sell oil to regions in which it would not make economic sense to ship to under normal market conditions, while requiring Europe to buy crude and products from non-Russian sellers that would not normally be the obvious choice. However, the measures have not so far caused significant disruptions of crude or product flows that may trigger extreme price spikes or even regional fuel shortages. This is not only due to the relatively lax nature of the G7-led measures outside Europe, but also down to the ability of the global oil and shipping industry to adapt quickly to changing conditions.

- There remains, however, a risk to markets in 2023. Should China’s economy recover faster from the recent Covid shock than initially anticipated (which seems likely) and Beijing provide consumer stimulus to kickstart its economy (as is expected), while the EU and US avoid a recession (which seems possible), the world’s three biggest oil consuming hubs could see higher oil consumption later this year than was initially expected. That could coincide with a decline in Russian oil production following the exodus of international firms and the lack of access to specialised western equipment that Russian oil producers require for maintenance work. While some other producers would likely be able to raise their output somewhat to compensate for declining Russian supply, it would probably lead to a tighter global market and higher prices for crude. This is especially the case as the two biggest other sources of crude, OPEC and the US, currently have limited upside. Most OPEC producers have little spare capacity and Saudi Arabia, the group’s de-facto leader, has an interest in defending relatively high crude prices. In the US, meanwhile, higher interest rates mean the highly leveraged shale industry and its lenders are less keen as they have been in the past to create new loans to finance more oil production.

Insights from Pamela Munger, Senior Market Analyst at Vortexa

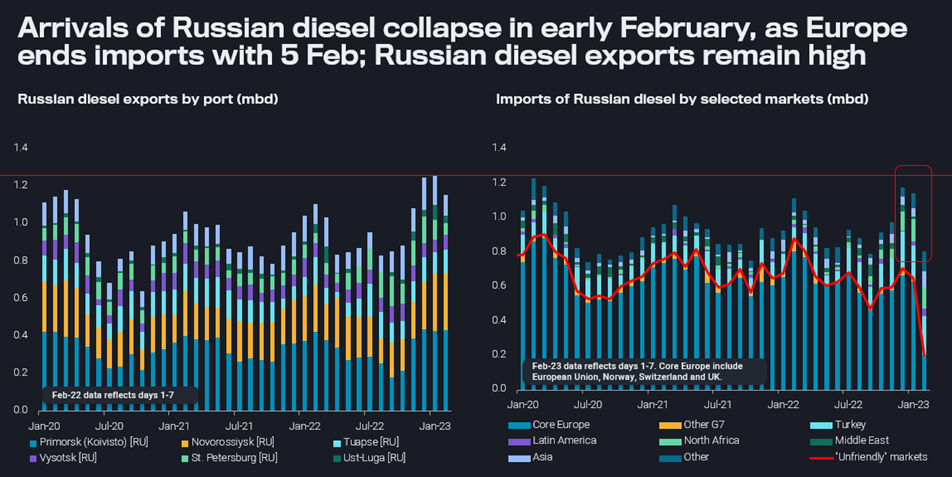

- In the months leading up to the clean products ban, Russian diesel exports to shorter haul destinations increased substantially as a drive to maximise profits before the start of the EU Russian refined products ban.

- “Non-traditional” markets have been found already in the early days for Russian diesel, such as Turkey, North Africa and Brazil. There are many markets to place diesel, much more than for crude.

- While it is easier to track larger vessels taking Russian crude, it will be much more difficult to track smaller vessels carrying refined products, especially if STS transfers are involved. There is also much less public interest in refined products.

- Looking at naphtha, Russia’s second biggest export behind diesel, we are seeing naphtha flows to Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea in larger volumes, often involving STS transfers.

Insights from David Wech, Chief Economist at Vortexa

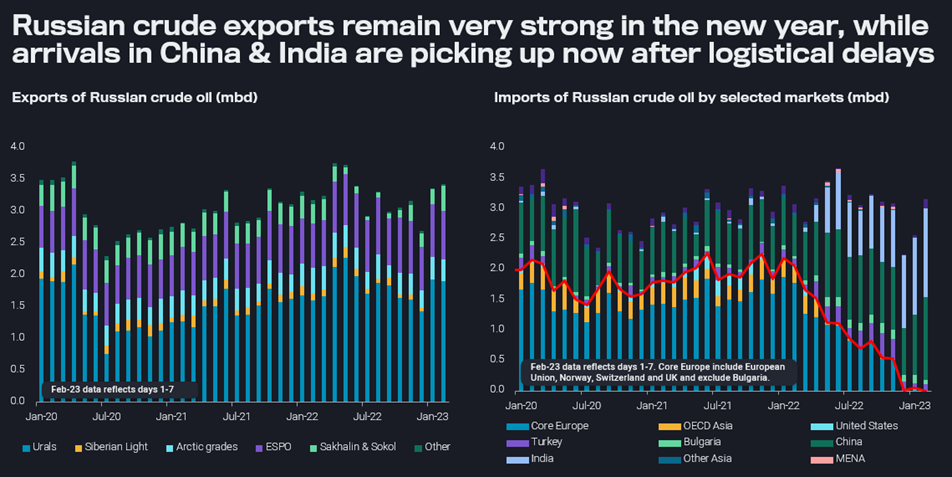

- Russian crude and product exports are running at a very high rate currently. However, the supply chain is getting much longer and there is currently twice as much Russian oil at sea than before the Ukraine war, making up 11% of all oil on the water.

- Oil income is crucial for Russia, and it can make much more money on a cargo of diesel than for crude exported via European waters. Therefore, Russia will keep diesel exports as high as they can.

Post webinar comment: Russia may well state otherwise in order to support outright prices. If diesel exports were to fall back to the seasonal norm by April, they would be 400kbd lower than actual exports in January. This normal development could well be “marketed” as deliberate cut.

- On the crude side, Russia is highly dependent on just two buyers, China and India, given massive pricing power to the latter.

Post webinar comment: any announced production cut is therefore hitting these two countries directly, which is somewhat delicate.

- We firmly believe there will be enough vessels to carry Russian clean products. A significant fleet has built up of Russian vessels combined with tankers over 15 years old sold in the past year. If necessary, coated dirty tankers can be cleaned up as well and used for the higher value products. It’s also worth noting that a reshuffling of flows does not necessarily mean higher vessel demand. E.g. Russia may serve North Africa in spite of Med Europe and Saudi Arabia may do exactly the reverse. Or LR tankers may move Russian diesel to the Wider Arabian Sea and take Indian or Middle Eastern diesel on the back-haul to Europe.

- Europe is well supplied with both crude and product. On crude there are many relative nearby suppliers like local producers, e.g. in Norway, North Africa or the Caspian, and mid-haul players like the US, West Africa and the Middle East. For product, 1.7mbd more diesel hit global markets in January, making the EU/Russian reshuffling need of 600kbd appear relatively tiny. Exporters are well prepared to serve the European market with on-spec product and a lot of new refining capacity is slated to come onstream in 2023.

- Current crude oil price, refinery margins and freight rate developments all suggest that oil demand cannot fare particularly well, suggesting that there is an impact from inflationary and recessionary pressures at least in Q1 2023.