Celebrating Black History Month: Q&A with Oliver Hypolite-Bishop

In celebration of Black History Month, Vortexa met with Oliver Hypolite-Bishop to learn more about the history and successes of the black community.

As October marks the beginning of Black History Month (BHM); a time dedicated to recognising the outstanding contributions and achievements of the black community, I wanted Vortexa to delve deeper into these critical issues and identify ways to heighten awareness for our teams throughout the business.

Oliver Hypolite-Bishop was a welcomed guest at Vortexa on the first Friday of BHM. As a political and social commentator and writer with a particular focus on the challenges of race, racism, class and inequality within Britain, Oliver has a specific interest in supporting youth and is an active contributor to the parliamentary commission on serious youth violence.

I invited Oliver to speak to Vortexa, to help us all learn what we as individuals can do to recognise, remember and champion the successes of the black community and to broaden our understanding of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement.

What motivated you to become a political activist and commentator for the black community?

To be honest, I think it was always a part of me, like an unshakeable sense of duty.

Whenever I am asked this question, I always think back to the conversations I used to have with my economics teacher in school. He would use his class to quiz my friends and I on the troubles in the local area; blessing us with unwanted analyses on the links between black boys and crime in Camden – removed from any data or evidence. I knew he was wrong, and his analysis was steeped in racism and not data. And so, as we argued on social issues beyond either of our comprehension, I felt compelled to understand and learn more about this inequality and racism that I could feel so vividly – but could not yet define.

So, as I chose to fight this thing called racism, I knew that if I was going to do so successfully, it would require me to understand not only the language and mechanics of racism, but to understand language itself – to understand politics, sociology, business and history.

That drive got me here. And while I do not pretend to hold a monopoly of knowledge on the topic, I feel immensely proud, and privileged, to share what little I know of this Black British history and experience.

I’ve gone on to give evidence to parliamentary commissions on serious youth violence, lobbied Prime Ministers, sat on boards, helped found charities and campaigns fighting for racial and social justice. All the things that once felt so foreign to the young boy from Camden.

Who are some black figures you have been inspired by throughout British history and why?

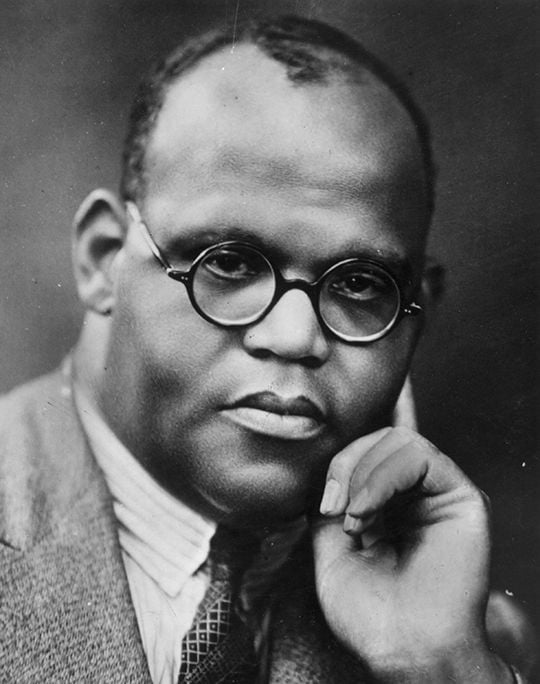

There are so many amazing characters throughout British history that we should know so much more about. These characters, and these stories, help us paint a more accurate picture of how diverse British society and culture has always been. I could talk of the Black Romans, Black Tudors, Black Georgians. The Black British war heroes of the many British wars. But, if I had to name but one, I would like to talk on Dr Harold Moody, the Jamaican-born, Peckham raised doctor who, in the 1930’s, established the League of Coloured People’s (LCP), with a mission to dismantle the ‘Colour Bar’, which was a series of policies and practices upheld by the unions and workers to refuse black people employment across key trades such as the railways and buses.

The LCP wasn’t just any group however, within its membership was the likes of Una Marson, the Jamaican poet, Paul Robeson, the American star athlete and concert artist, Jomo Kenyatta who would become the anti-colonial Prime Minister of Kenya in the 60’s, C.L.R James the British-Trinidadian author of the Black Jacobins. It was the NAACP of the UK.

Moody overturned the Special Restriction Order (aka the Coloured Seamen’s Act) of 1925; a discriminatory measure that sought to provide subsidies to merchant shipping employing only British nationals and required alien seamen (many of whom had served the UK during WW1) to register with their local police.

Dr Moody was eventually appointed to a government advisory committee on the welfare of non-Europeans in 1943 but died just four years before the arrival of HMS Windrush. Moody helped set into motion a century of black activism and protest that dismantled not just the Colour Bar but helped forge the civil rights policy landscape that we today use as evidence of our British liberal values.

What is your biggest challenge as an activist?

People are particularly divided at the moment, we sit at opposite ends. If we talk about racism, it quickly escalates and reverts back to socialism and class issues. Take Piers Morgan, the way he converses with activists on his show Good Morning, he points fingers at them, he is foaming at the mouth and this sort of conversation isn’t helpful. It’s not this binary ‘agree or disagree’ subject; we need complete openness.

What is good for the black community – is good for all of us. There should be no particular reason anyone would be in opposition to creating a more equal and less racist society. So, a big challenge is trying to demonstrate the parallels in our lives with people who think they are on the ‘opposite sides’ of the argument but they are not – they want the same things. It’s just finding the right words to communicate that.

What do you think the education system can do more of to help the black community?

While most teachers are able to teach black history, many don’t feel particularly well equipped to do so. So, when it comes to teaching black history, many teachers revert to Nelson Mandela, or American civil rights, rather than the British civil rights story we should be telling.

Black history, as the saying goes, is British history. And British history is an international one. Therefore, I would like to see this international, honest, open and inclusive version of our history taught in our schools as part of our national curriculum. One of the challenges we will face however, is that in this age of unfounded culture wars, and accusations of ‘erasing history’, the very goal of trying to teach this whole history is regarded as almost unpatriotic – we don’t like to speak bad of our imperial past so instead we just sweep all that bad bits under the rug. Importantly, this isn’t just about helping the black community however, this history is for all of us.

We also need to stop permanently excluding children, particularly when they are in vulnerable environments. It’s become such an issue, that disproportionately impacts black children, that it has come to be known as the PRU (pupil referral unit)-to-prison pipeline. Unable to handle naughty kids, we throw them into the system and outside of the safety of mainstream education. This isn’t an issue just for black kids, but for all working class kids who are deemed ‘unteachable’. We need to stop telling kids they are criminals and throw them into the criminal justice system. They need support and to be kept in education.

How do you bring deeper context to a wider population?

Conversations, such as this, are a pretty good start. But we need to get these conversations about our history into wider society. It’s not something that will happen overnight. However, a large part of the challenge is that whenever we reach pivotal moments such as this, we still fall back to the same reductive question, Is Britain Racist?

It turns an argument about structures and systemic racism into one about individuals. If the answer is yes, then the insinuation is that all British white people are ‘bad people’ instead of an exploration into the institutions that uphold the ethnic penalty of race and class in a very unequal Britain. And because of that politicians will be quick to deny that ‘Britain is racist’. With this question the media has always felt compelled to present a discussion in a binary debate between two opposing sides; one who believes in racism versus another that doesn’t.

Yet, when the prevalence of racism is exemplified so clearly in data, lived experiences and in the history of black activism, this question feels very juvenile and particularly unhelpful in helping the country understand racism in a deeper context while only fuelling fears of ‘culture wars’. Racism isn’t a question, or debate, and until we can move beyond that basic question we will remain stuck.

History is a tool for social justice. We build our national identities off the back of history – so we need to stop building them off existing, half-truths of lovely tolerant Britain who knows nothing of racism – because that script isn’t changing, and it certainly isn’t helping.

What positive turning points have you seen in society?

I think we are in a good place at the moment. For the first time in a long time the conversations are heading in the right direction. The allies of black movements move alongside us and understand that for this movement to be meaningful they must provide the spaces, like this, for us to speak while not trying to speak for us.

Young people are far more likely to disregard any notion of racism and go against racist views held by previous generations. But the greater issues aren’t among the conversations had on the streets, it’s the long-standing institutions that continue to create and uphold an environment that negatively impacts different ethnic minorities.

Businesses and organisations that began their response to BLM with vacuous posts, hashtags, and black squares are now realising that without action their ally-ship is nothing more than virtue signalling, and they will be called on it.

As statues topple and plans for new ones emerge, the black story of the past century is beginning to come to light. To build a statue to honour black history, we first need to learn who our black heroes are.

There are campaigns to teach a more inclusive, more diverse history in our schools, beyond Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela. This is a positive step forward.

Finally, what actions do you think we can all take to help drive social change and support the black community?

A significant message from the uprisings during the summer was that condemning racism alone is not enough. Making this moment meaningful requires all of us to get off the sidelines and become actively anti-racist. This means listening, learning and challenging our own biases or discrimination where we see it, whether it is in the workplace or in society. Anti-racism isn’t just something that helps the black community but benefits us all.

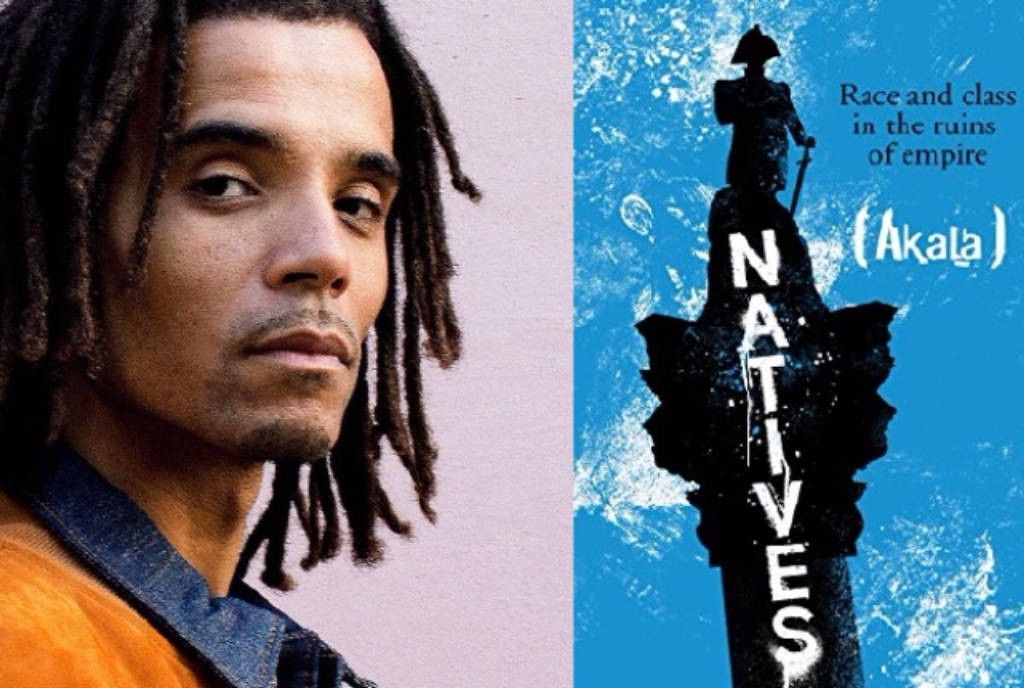

I would also say it’s a good moment to take the time to read and learn. I would always recommend the writing and words of fellow Camden local, Akala and his book Natives. David Olusoga and Afua Hirsch have written about the extensiveness of black history and imperialism which is also worth an exploration. And finally, to really understand the lived experience of Black Britain I say look no further than George the Poet’s incredible podcast ‘Have you heard George the Poet’s podcast?’

Author Akala and his novel ‘Natives’

Author Akala and his novel ‘Natives’

As a company we are always striving to build on the inclusive culture we have built to date and strengthen our understanding of societal changes, whilst remaining mindful of the challenges faced by black and minority ethnic communities.

We are always keen to learn more and to shine the spotlight on the crucial issues within society that deserve our attention. Oliver shared invaluable insights and proactive takeaways that we as a company will take onboard to better ourselves as a business and as individuals; striving for an inclusive society that aims for equity of treatment for all.

Follow Oliver on social media:

LinkedIn

Twitter