Many market commentators suggest that the diesel reshuffling, necessary with the EU Russian product import ban taking place on Feb 5, will be more challenging than the relatively easy sailing on the crude oil side. While there is surely a lot of uncertainty ahead, we will raise in this blog a couple of factors suggesting a smooth transition on diesel as well. High Russian crude and product exports can only be sustained if buying interest and vessel supply matches consistently the outflows. This can only be judged after 3-5 months into the ban, with a doubling of Russian oil on the water at least raising some question marks.

Lessons learnt from crude

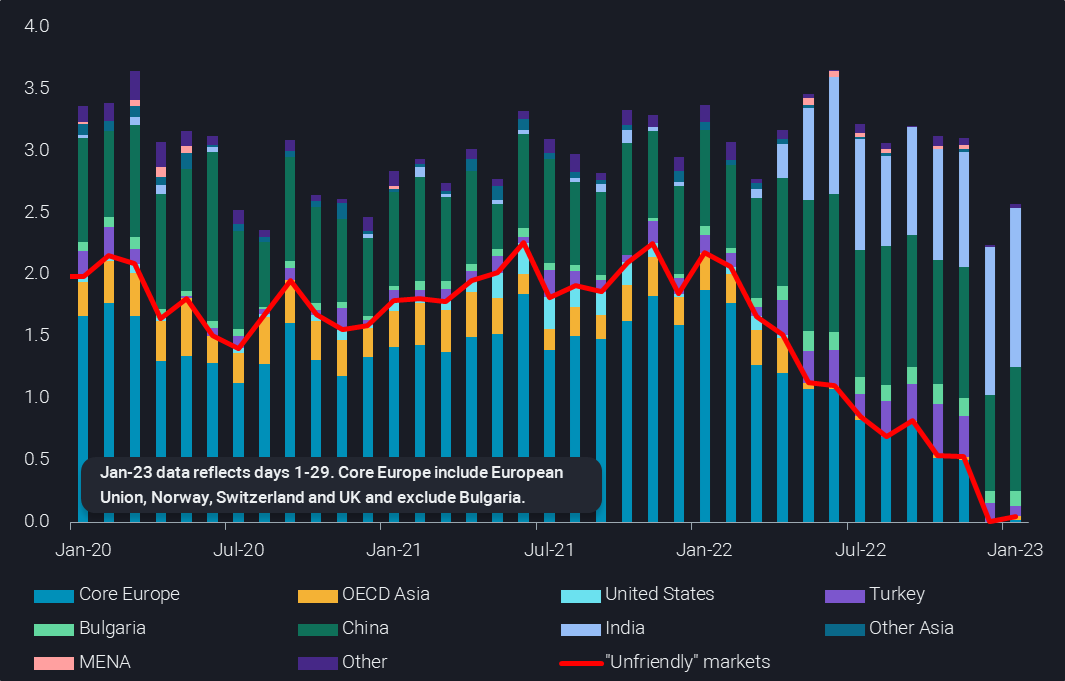

It is nearly two months since the European Union’s seaborne imports of Russian crude have come to a halt (with the exception of Bulgaria). The widespread sanction scheme also limits the use of EU vessels, insurance and other services for Russian oil exports to third parties. While seaborne exports of Russian crude oil temporarily dipped by 500kbd or 15% m-o-m in December according to Vortexa data, they are staging a strong comeback in January, and are set to end the month higher than in November.

On the buying side, India has become the biggest importer of Russian crude oil, taking between 1.2-1.3mbd over the last two months. China hesitated in December, but inflows are back to about 1.1mbd in January. Only some 200kbd are going to other countries, including Turkey, which has cut back its purchases to less than 100kbd in January, after levels of 300-400kbd in the months before the EU import ban.

The switch in destinations is coming along with substantial changes in the logistical chain. First of all, most shipments are now handled by a mix of players based in Russia, India, China and the Middle East – in the case of the latter three, these firms are often new market entrants. Before the war, Western majors and European companies were mostly in charge of these flows. The other big change is the trips are now of course much longer and partly also more protracted. This means that much more vessel capacity is required. Finally, to ensure vessel availability (for Aframaxes and Suezmaxes) and partly also to disguise the origin of the crude, ship-to-ship transfers are becoming much more frequent. More than 20% of Russian crude exports via Europe are now transferred from smaller feeder vessels to VLCCs, mostly offshore Ceuta in the Western Mediterranean or in the Kalamata area off Greece.

Economic incentives should keep Russian diesel flowing

So the question is whether the situation is more or less difficult for diesel? Starting with shipping, similar to dirty tankers, new market entrants have also bought up a sizeable fleet of clean tankers. And on the clean side it would be even easier to transition from the usual smaller MR vessels to bigger LR1 or LR2 vessels, while in the worst case dirty vessels could be cleaned up.

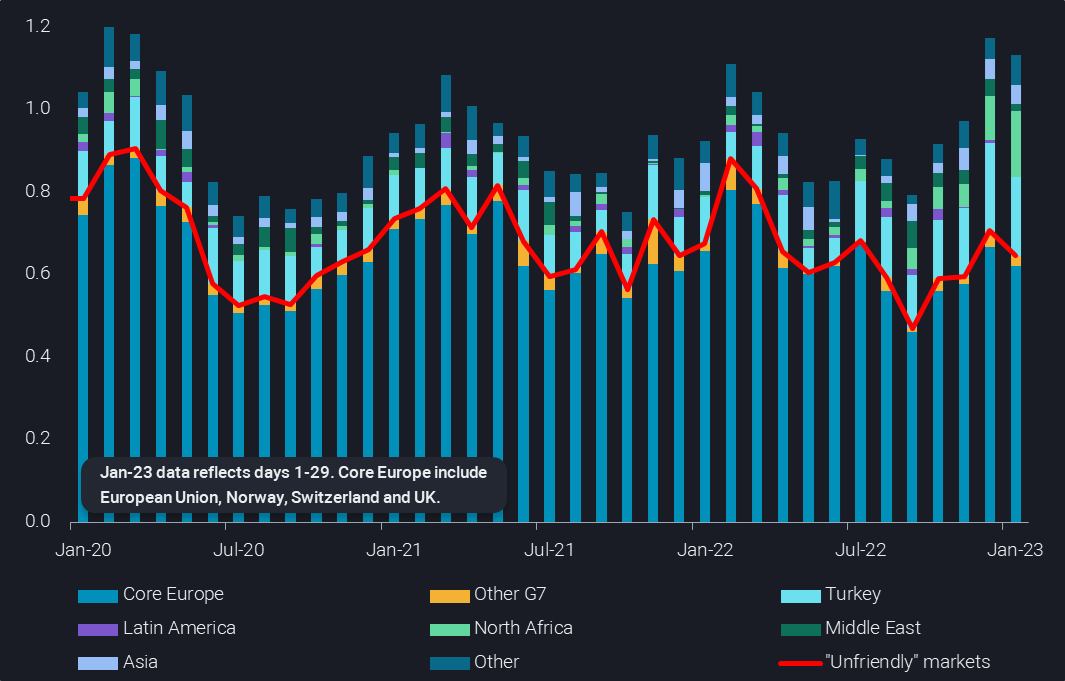

North African countries have already started to increase imports of Russian diesel, but some 600kbd still need to be rerouted away from core European buyers. Another 200kbd of other clean products comes on top of this, which will easily follow the path of 400kbd already moving to places around the world, with a clear focus in East of Suez markets.

The 600kbd diesel reshuffling need compares favourably to imports of 1.5mbd into Africa and the Middle East from external sources, of which Russia serves less than 200kbd so far. These markets have so far been serviced largely by Asia, European and Middle Eastern players, which could in exchange supply the open European needs.

This means that the additional vessel needs may be limited. To illustrate, Morocco took more than 60% of its diesel imports from Russia, and largely eliminated Saudi diesel, which topped the list in 2022 with a market share of 45%. Now the Saudi barrels will likely find homes in European countries, adding relatively little ton-mileage overall. Also, new round-trips may materialise – e.g. Russian diesel could go to East Africa and on the back-haul Middle Eastern or Indian diesel may be carried to Europe. EU shipping and service sanctions may complicate this, but also increase the incentive to make use of the price cap mechanism. Bigger vessel classes and more STS transfers may also help.

This raises the question of whether Russia may cut exports, out of some mix of retaliation, deep discounts and poor refining economics. Unlikely, given the transition to a cash-stripped war economy, with the current flood of exports also illustrating the Russian eagerness to sustain exports. As for diesel specifically, it is important to keep outright price levels in mind.

Russian exporters are likely still getting more than $100/b for diesel, in spite of deepening discounts and stagnating prices, while for Urals this is often in the order of $40/b (Argus Media). So diesel alone may be able to carry the full weight of Russian refining economics and fuels like naphtha or fuel oil may be given away for nearly arbitrarily low prices, just to keep refineries running if necessary. It is furthermore not a given that Russia could easily shift exports from products to crude, as it has only two main buyers for the latter and faces limitations on infrastructure.

After all, high $/b sales prices will motivate the Russian side and massive discounts will stimulate much more diversity in buyers, especially if the price mechanism is partially employed, enabling established players to take care of the logistics. And the latter does not necessarily have to be (officially) visible to Russian authorities.

Finally, the reshuffling pattern is set to change in the near future, ensuring also that European buyers get the diesel they need. Over the last four months, Europeans have bought 400kbd more than they usually need, as Russian flows continued while replacement barrels were already coming in. Given the relatively mild winter and its progression, easing gas/power markets, as well as growing signs of at least a mild recession, European demand is set to ease. This and the volumes being freed up in other markets (that are finally hit by Russian diesel) may well help to ease diesel market tightness.

Russian oil at sea doubling – necessity or warning flag?

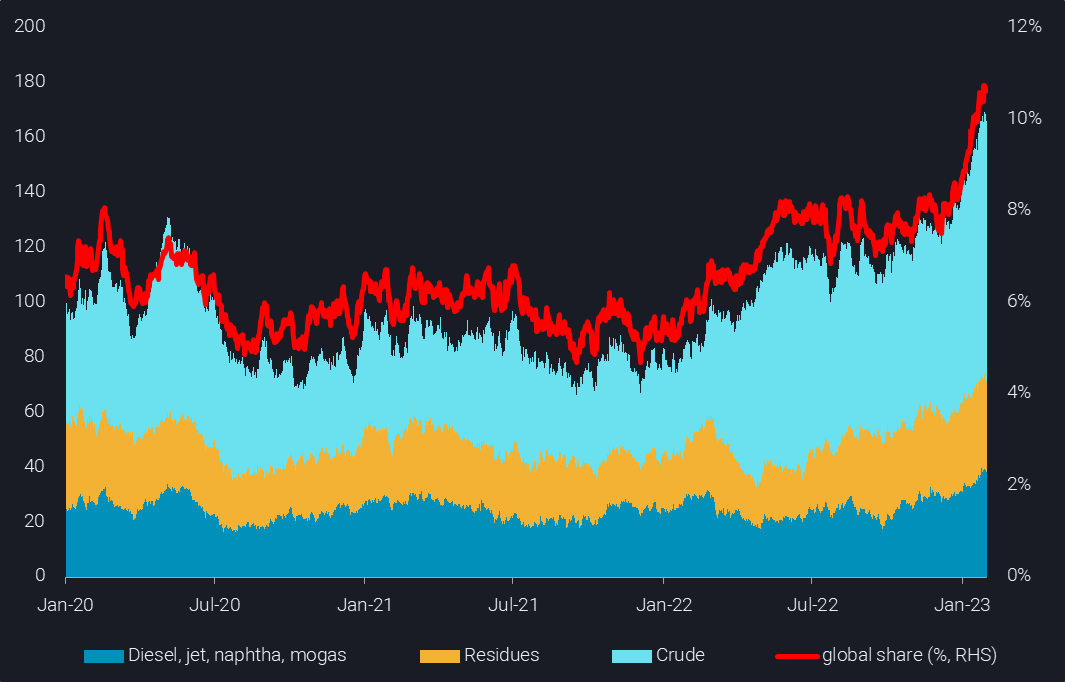

About 165 million barrels of Russian oil are currently on the water, some 93mb of crude, 38mb of clean products and 34mb of residues. This is twice as high as the 2021 average, with crude up 165% and products up about 50%. Russian oil is now rising to make up 11% of global oil at sea, compared to historical lows below the 5% mark.

Of course there is a good reason for this. If Urals and other streams are moving to India and China, rather than Germany and Italy, transit times are way longer. But the recent surge of Russian oil on the water also serves as a warning signal that not every vessel that leaves a Russian port has necessarily already a willing buyer. For instance, imports of Russian crude in January are falling 700kbd behind Russian exports. In other words, high export flows in the early days of full sanctions are not necessarily sustainable. Apart from missing buyers a lack of vessels may still emerge at a later point in time, as a “shadow fleet” vessel may only pick up the next cargo in about four months (or more if it gets stuck).

Russian oil on the water by type (mb, LHS) & share in global total (%, RHS)